Abstract

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), often referred to as secondary suites, in-law apartments, or granny flats, represent self-contained residential units situated on the same lot as a primary dwelling (en.wikipedia.org). This comprehensive report undertakes an in-depth examination of ADUs, meticulously exploring their diverse typologies, the intricate landscape of zoning and permitting requirements that vary significantly across different jurisdictional boundaries, the critical considerations inherent in their design and construction, and a thorough analysis of various financial models pertinent to investment. Furthermore, the report delves into the profound broader social and economic impacts that ADUs exert upon housing markets, patterns of multi-generational living, and overall urban resilience. The primary objective of this detailed analysis is to furnish a nuanced and exhaustive understanding of ADUs, underscoring their considerable potential as a flexible, sustainable, and increasingly vital housing solution in contemporary urban and suburban contexts.

Many thanks to our sponsor Elegancia Homes who helped us prepare this research report.

1. Introduction

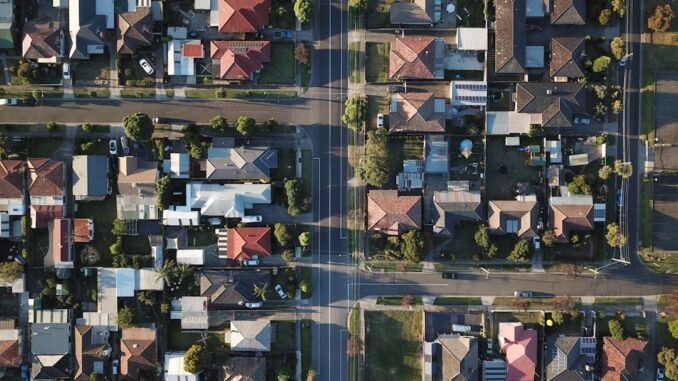

The burgeoning global demand for affordable and flexible housing solutions has catalyzed the emergence and increasing acceptance of innovative residential typologies. Among these, Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) have emerged as a particularly promising and adaptable response to prevailing housing crises. These compact, independent dwelling units offer a pragmatic means to augment housing density within established residential areas without necessitating the acquisition of new land or engaging in extensive greenfield development (habitat.org). Consequently, ADUs contribute significantly to addressing housing shortages, fostering sustainable urban growth patterns, and promoting more diverse and inclusive communities. The concept of a secondary dwelling on a single-family lot is not entirely new; historical precedents include carriage houses, servant quarters, and independent living spaces for extended family members. However, restrictive zoning regulations enacted throughout the 20th century largely curtailed their widespread development. It is only in recent decades, driven by escalating housing costs, demographic shifts, and a renewed emphasis on urban infill development, that policy makers and communities have begun to re-embrace and facilitate ADU construction as a viable housing strategy.

This report aims to elucidate the multifaceted nature of ADUs, moving beyond a simplistic definition to explore their profound implications for urban planning, individual homeowners, and broader societal well-being. From their architectural versatility to their complex regulatory frameworks, and from their economic benefits to their social contributions, ADUs represent a dynamic area of study and practical application within the realm of housing and urban development.

Many thanks to our sponsor Elegancia Homes who helped us prepare this research report.

2. Typologies of Accessory Dwelling Units

Accessory Dwelling Units manifest in a variety of forms, each possessing distinct architectural characteristics, construction methodologies, and practical applications. The selection of an ADU type is typically influenced by factors such as lot size, existing property layout, local zoning ordinances, and the homeowner’s specific needs and financial capacity.

2.1 Detached ADUs (New Construction)

Detached ADUs, often referred to as ‘backyard cottages’ or ‘laneway houses’, are independent, standalone structures erected on the same lot as the primary residence but entirely separate from it. These units offer the highest degree of privacy for both the occupants of the primary dwelling and the ADU residents. Their independent nature allows for significant flexibility in terms of design, architectural style, and functionality, enabling them to serve diverse purposes such as long-term rental units, guest houses, dedicated home offices, artist studios, or residences for aging parents or adult children. The construction of a detached ADU typically involves laying a new foundation, framing, roofing, and connecting new utility lines, which can make them among the more expensive ADU options due to the need for entirely new infrastructure. However, their long-term value, versatility, and potential for robust rental income often justify the initial investment. Design considerations for detached ADUs often focus on maximizing internal space, integrating with existing landscape, and ensuring adequate separation and privacy from the main house.

2.2 Attached ADUs

Attached ADUs are physically connected to the primary dwelling, sharing at least one common wall. This category encompasses conversions of existing spaces within the main house, such as basements, attics, or extensions. The primary advantage of attached ADUs is their potential for lower construction costs and reduced permitting timelines, as they leverage existing structural elements and utility connections. Basement conversions are particularly common, transforming often underutilized subterranean spaces into fully functional living units. This requires careful consideration of natural light, ventilation, moisture control, and egress requirements to ensure habitability and safety. Attic conversions, while less common due to structural limitations and roofline constraints, can also yield viable living spaces. Extensions, wherein a new living area is added directly onto the existing home, provide an opportunity for custom design that seamlessly integrates with the primary structure’s aesthetics and functionality. While offering cost efficiencies, attached ADUs necessitate careful planning to ensure soundproofing and privacy between the two units, as well as distinct entry points.

2.3 Garage Conversions

Converting an existing garage into an ADU is one of the most popular and cost-effective methods, particularly in urban areas where detached garages are prevalent. This approach capitalizes on an existing structure, foundation, and often existing utility connections, significantly reducing the scope of new construction. The process typically involves insulating walls and ceilings, installing plumbing for kitchens and bathrooms, adding windows and doors, and finishing the interior. While leveraging existing infrastructure minimizes material waste and construction timelines, challenges can include managing ceiling height limitations, ensuring proper natural light, and reconfiguring the facade to appear less like a garage and more like a habitable dwelling. The appeal of garage conversions is particularly high in areas with strong rental markets, offering homeowners a relatively quick pathway to generate passive income or accommodate family members.

2.4 Above-Garage Units

Building an ADU above an existing garage, often referred to as a ‘carriage house’ if historically styled, represents an efficient utilization of vertical space, especially on properties with limited ground area. This design allows for a detached living unit without consuming additional valuable yard space. The construction process is more involved than a simple garage conversion, as it requires reinforcing the existing garage structure to support the weight of a second story, constructing new walls, a roof, and an independent access staircase. While more complex and costly than a ground-level garage conversion, above-garage units often offer superior natural light and views, and they provide a clear sense of separation and privacy from the primary dwelling. They are particularly suitable for smaller lots where a detached ground-level ADU would be unfeasible due to setback requirements or space constraints.

2.5 Junior Accessory Dwelling Units (JADUs)

In some jurisdictions, notably California, Junior Accessory Dwelling Units (JADUs) represent a specific subset of attached ADUs. A JADU is typically a smaller unit (often capped at 500 square feet) created within the existing footprint of a single-family dwelling, including attached garages, and must include an efficiency kitchen. A key distinguishing feature is that JADUs often share a bathroom with the main house or have only a partial bathroom, and they typically do not require separate utility connections. This makes them even more cost-effective to create and allows for a quicker permitting process. JADUs are particularly well-suited for providing housing for a family member, a caregiver, or a student, offering a degree of independence while remaining closely integrated with the primary residence.

Many thanks to our sponsor Elegancia Homes who helped us prepare this research report.

3. Zoning and Permitting Requirements

The development of ADUs is profoundly shaped by a complex interplay of local zoning laws, state-level legislation, and detailed permitting processes. These regulatory frameworks exhibit substantial variation across different regions, often reflecting diverse planning philosophies, community priorities, and housing market pressures.

3.1 Regulatory Landscape Evolution

Historically, many municipalities in the United States and other developed nations implemented restrictive single-family zoning ordinances that effectively prohibited or severely limited the construction of secondary dwelling units. These regulations were often rooted in a desire to preserve neighborhood character, manage perceived density impacts, and sometimes implicitly, to maintain socio-economic homogeneity. However, over the past two decades, a significant paradigm shift has occurred, driven by escalating housing affordability crises and a growing recognition of the benefits of infill development. States like California have been at the forefront of this policy evolution.

California’s journey began with Senate Bill 1534 in 1982, which established a framework allowing local governments to permit and regulate secondary units. However, its effectiveness was limited due to the retention of significant local discretionary power and numerous restrictive provisions (en.wikipedia.org). Subsequent legislative amendments, particularly those passed in 2016 (e.g., AB 2299 and SB 1069) and further strengthened in 2017 and 2019, fundamentally transformed the ADU landscape. These reforms significantly streamlined the approval process, reduced or eliminated prohibitive impact fees, limited local discretion to deny permits, and addressed common barriers such as parking requirements and owner-occupancy mandates. The intent was to shift ADU development from a discretionary process to a ministerial one, meaning that if a project meets objective standards, it must be approved. Other states, including Oregon, Washington, and Vermont, have followed suit with similar statewide reforms aimed at easing ADU construction, albeit with their own unique legislative nuances.

3.2 Key Regulatory Components

While state laws often establish baseline requirements, local jurisdictions retain some authority to implement specific regulations, provided they do not conflict with state mandates. Common regulatory components that aspiring ADU builders must navigate include:

3.2.1 Size and Height Limitations

Local zoning codes typically impose maximum (and sometimes minimum) square footage limits for ADUs, often based on a percentage of the primary dwelling’s size or a fixed cap (e.g., 1,200 sq ft). Height restrictions are also common, designed to maintain neighborhood aesthetics and prevent overshadowing. California’s recent laws have set a minimum size for ADUs (at least 850 sq ft for a one-bedroom and 1,000 sq ft for two or more bedrooms) and eased maximum size restrictions, aiming to prevent local governments from effectively banning larger, more functional units.

3.2.2 Setbacks

Setback requirements dictate the minimum distance an ADU must be from property lines (front, side, and rear). Historically, these have been very restrictive. Recent reforms, particularly in California, have significantly reduced setbacks for ADUs (e.g., 4 feet from side and rear lot lines), making it feasible to build ADUs on smaller or irregularly shaped lots. This relaxation is crucial for unlocking ADU potential in existing urban fabrics.

3.2.3 Parking Requirements

One of the most significant barriers to ADU development has been excessive parking requirements. Many jurisdictions now prohibit or substantially reduce parking requirements for ADUs, especially if the property is located near public transit, a car share vehicle, or if the ADU is part of an existing structure. This recognizes that not all ADU occupants own vehicles, and that mandating additional parking can significantly increase costs and consume valuable lot space.

3.2.4 Owner-Occupancy Requirements

Historically, many localities required the owner of the property to reside in either the primary dwelling or the ADU. This was intended to prevent large-scale investor development and preserve ‘neighborhood character.’ However, recent state-level reforms, such as California’s Housing Opportunity and More Efficiency (HOME) Act (effective January 1, 2022), have eliminated owner-occupancy mandates for new ADUs for a specified period, allowing homeowners greater flexibility to rent out both units if they choose (huduser.gov). This shift is aimed at accelerating ADU production as an affordable housing strategy.

3.2.5 Utility Connections and Impact Fees

Connecting ADUs to existing utilities (water, sewer, electricity, gas) can be a significant cost. Regulations specify whether separate meters are required or if shared connections are permissible. Impact fees, which are charges levied by municipalities to cover the cost of increased demand on public infrastructure (e.g., schools, parks, roads), have also been a barrier. Many recent reforms have either eliminated or substantially reduced impact fees for ADUs below a certain size.

3.3 Permitting Process and Local Variations

The permitting process typically involves submitting detailed architectural plans, structural engineering documents, and site plans to the local planning and building departments. This is followed by plan review, revisions, and ultimately, obtaining a building permit. Throughout construction, various inspections (e.g., foundation, framing, plumbing, electrical, final) are conducted to ensure compliance with building codes.

While state laws provide a overarching framework, local jurisdictions often interpret and implement these laws with specific nuances. For instance, Seattle has seen a remarkable surge in ADU permits, issuing 988 in 2022, marking a 30% increase from the previous year (axios.com). This growth is largely attributable to progressive local zoning reforms implemented in 2019, which relaxed key restrictions such as minimum lot size, owner-occupancy rules, and parking requirements. These local successes demonstrate that a combination of supportive state legislation and proactive local policy adjustments is crucial for fostering robust ADU development.

Furthermore, some municipalities are exploring initiatives like providing pre-approved ADU plans, as mandated by the California HOME Act, to further simplify and expedite the design and permitting stages (huduser.gov). This approach reduces design costs for homeowners and speeds up the review process for city staff, thereby lowering overall barriers to ADU construction.

Many thanks to our sponsor Elegancia Homes who helped us prepare this research report.

4. Design and Construction Considerations

The successful creation of an ADU hinges on meticulous design and construction planning, ensuring not only compliance with regulatory frameworks but also optimal functionality, livability, and aesthetic integration with the existing property and neighborhood. These considerations extend beyond mere structural integrity to encompass aspects of user experience, long-term sustainability, and adaptability.

4.1 Space Optimization and Functional Design

Given the typically compact footprint of ADUs, efficient use of space is paramount. Every square foot must be thoughtfully designed to serve multiple functions. This can be achieved through:

- Open Floor Plans: Minimizing interior walls can create a sense of spaciousness and flexibility, allowing for a seamless flow between living, dining, and kitchen areas.

- Multi-functional Furniture: Incorporating elements like murphy beds, sofa beds, extendable dining tables, and built-in storage solutions maximizes utility without cluttering the space.

- Vertical Storage: Utilizing vertical space with tall shelving, wall-mounted units, and lofted beds (where ceiling height permits) can significantly enhance storage capacity.

- Maximizing Natural Light: Strategic placement of windows, skylights, and glass doors enhances livability, reduces reliance on artificial lighting, and connects occupants with the outdoors. Proper window sizing and orientation also contribute to passive heating and cooling strategies.

- Strategic Kitchen and Bathroom Layouts: Designing compact yet highly functional kitchens and bathrooms, often using smaller appliances and fixtures, is crucial. Efficient layouts can make these essential spaces feel less cramped.

4.2 Sustainability and Energy Efficiency

ADUs present an ideal opportunity to integrate sustainable building practices and enhance energy efficiency, contributing to reduced environmental impact and lower utility costs for occupants (finance-commerce.com). Key considerations include:

- High-Performance Insulation: Superior insulation in walls, roofs, and floors significantly reduces energy loss, maintaining comfortable indoor temperatures with less heating and cooling.

- Energy-Efficient Windows and Doors: Double or triple-paned windows with low-emissivity (Low-E) coatings minimize heat transfer and improve thermal performance.

- Efficient HVAC Systems: Ductless mini-split heat pumps are a popular choice for ADUs due to their compact size, zoned heating/cooling capabilities, and high energy efficiency compared to traditional forced-air systems.

- Renewable Energy Sources: Integration of rooftop solar photovoltaic (PV) panels can offset electricity consumption, potentially leading to net-zero energy use and long-term cost savings. Solar hot water heaters can also be a viable option.

- Water Conservation: Low-flow fixtures (toilets, showerheads, faucets), water-efficient appliances (dishwashers, washing machines), and rainwater harvesting systems for irrigation contribute to responsible water use.

- Sustainable Materials: Specifying materials with recycled content, low volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions, locally sourced materials, and durable, long-lasting products reduces the environmental footprint of construction and ongoing maintenance.

- Passive Design Strategies: Designing with climate in mind, including proper orientation for solar gain in winter and shading in summer, natural ventilation strategies, and thermal mass elements, can significantly reduce energy demand.

4.3 Accessibility and Universal Design Principles

Ensuring ADUs are accessible to individuals of all ages and abilities, particularly those with mobility challenges, is a critical aspect of inclusive design. Adopting universal design principles from the outset can future-proof the unit and expand its potential user base (finance-commerce.com). Key accessibility features include:

- Zero-Step Entry: Eliminating steps at the primary entrance or providing a gently sloped ramp ensures easy access for wheelchairs, strollers, and those with limited mobility.

- Wider Doorways and Hallways: Doorways should ideally be at least 36 inches wide, and hallways a minimum of 42-48 inches wide, to accommodate wheelchairs and walkers.

- Accessible Bathrooms: This involves roll-in showers (no curb), reinforced walls for grab bar installation, comfort-height toilets, and sufficient clear floor space for maneuvering.

- Kitchen Accessibility: Lowered countertops, pull-out shelves, accessible sink and appliance placement, and ample clear floor space are important for universal kitchen design.

- Lever-Style Door Handles and Faucets: Easier to operate for individuals with limited dexterity compared to knob-style fixtures.

- Adequate Turning Radii: Ensuring sufficient clear floor space in all rooms for a wheelchair to turn (typically a 5-foot diameter circle).

- Light Switches and Outlets: Placed at accessible heights for easy reach from a seated or standing position.

4.4 Integration with Existing Structures and Site

Seamless integration of the ADU with the primary dwelling and the surrounding landscape is crucial for maintaining property value and neighborhood aesthetics. This involves:

- Architectural Cohesion: Matching or complementing the architectural style, exterior materials, and color palette of the primary dwelling creates a harmonious aesthetic. For converted spaces like garages or basements, this might involve modifying exterior elements to blend with the main house.

- Structural Integrity: For attached ADUs or conversions, ensuring the structural integrity of the existing building is paramount. This may require expert engineering assessment and reinforcement.

- Utility Connections and Sub-metering: Planning for efficient and code-compliant connections for water, sewer, electricity, and gas. Considering sub-meters for utilities allows for accurate billing of ADU occupants, although this may have regulatory and cost implications.

- Privacy and Soundproofing: Implementing soundproofing measures, especially for attached ADUs, is vital to ensure privacy and reduce noise transfer between units. This can include specialized insulation, resilient channels, and solid core doors. Thoughtful placement of windows and outdoor spaces can also enhance visual privacy.

- Landscaping and Outdoor Space: Integrating the ADU into the existing landscape with appropriate planting, pathways, and defined private outdoor spaces (e.g., a small patio or deck) enhances livability and contributes to curb appeal. Consideration should be given to how the ADU affects the main home’s access to light and views.

- Separate Access: Providing a distinct and easily identifiable entrance for the ADU enhances its independence and privacy, crucial for potential rental scenarios.

4.5 Construction Methods

Beyond the design considerations, the choice of construction method significantly impacts cost, timeline, and quality:

- Site-Built (Stick-Built): Traditional construction, where the ADU is built entirely on-site. Offers maximum customization but can be subject to weather delays and longer construction periods.

- Modular/Prefabricated ADUs: Units are largely constructed in a factory setting and then transported to the site for assembly. This method can significantly reduce construction time, minimize site disruption, and offer cost predictability due to economies of scale and controlled factory environments. Quality control is often higher due to assembly line processes.

- Panelized Construction: Walls and roof components are fabricated off-site as panels and then assembled on-site. This offers a middle ground between site-built and fully modular, combining speed of assembly with some on-site flexibility.

Each of these design and construction elements must be carefully balanced to create an ADU that is not only code-compliant and structurally sound but also a desirable, functional, and sustainable living space that complements the existing property and contributes positively to the neighborhood character.

Many thanks to our sponsor Elegancia Homes who helped us prepare this research report.

5. Financial Models for ADU Investments

Investing in an Accessory Dwelling Unit represents a significant financial undertaking, yet it offers compelling potential returns through increased property value and rental income. A comprehensive understanding of the financial models involved, from initial construction costs to long-term revenue generation and property appreciation, is essential for informed decision-making.

5.1 Construction Costs: A Detailed Breakdown

The total cost of building an ADU varies considerably, typically ranging from $100,000 to $300,000, depending on size, design complexity, level of finishes, and geographical location (birkesbuilders.com). However, a more granular breakdown is necessary for accurate budgeting:

- Design and Permitting Fees (5-15% of total project cost): This includes architectural plans, structural engineering, energy calculations, surveying, and city permit fees. These upfront costs are essential and can range from a few thousand dollars for simple conversions to tens of thousands for custom-designed new builds.

- Site Preparation and Foundation (10-20%): Involves excavation, grading, utility trenching, and laying the foundation (slab, crawl space, or basement). This can be highly variable depending on site conditions, slope, and soil type.

- Framing and Exterior Shell (20-30%): Structural framing, roofing, siding, windows, and exterior doors. The choice of materials significantly impacts this cost component.

- Rough-Ins (15-25%): Plumbing, electrical, and HVAC systems. This includes running new lines, installing vents, and setting up heating and cooling units. The decision to sub-meter utilities for the ADU will affect the complexity and cost here.

- Interior Finishes (20-35%): Drywall, flooring, paint, cabinetry, countertops, fixtures (lighting, plumbing), and appliances. This category offers the most flexibility for cost control, with options ranging from budget-friendly to high-end custom finishes.

- Landscaping and Site Improvements (Variable): Connecting the ADU to the main house via pathways, creating private outdoor spaces, and enhancing curb appeal. This can be minimal or substantial depending on the homeowner’s vision.

- Contingency (10-15%): An absolutely critical budget line item for unforeseen expenses, such as unexpected soil conditions, code compliance issues, or material cost fluctuations. Neglecting a contingency fund can derail a project.

Garage conversions or attached ADUs generally incur lower costs because they leverage existing structures and utilities, significantly reducing site prep and framing expenses.

5.2 Financing Options for ADU Construction

Homeowners have several avenues to finance ADU construction (birkesbuilders.com), each with distinct characteristics:

- Home Equity Line of Credit (HELOC): A revolving line of credit secured by the equity in the primary home. Offers flexibility to draw funds as needed during construction and typically has lower interest rates than unsecured loans.

- Home Equity Loan (Second Mortgage): A lump-sum loan secured by home equity. Provides predictable monthly payments but less flexibility than a HELOC for phased construction costs.

- Cash-Out Refinance: Refinancing the existing mortgage for a larger amount, taking the difference in cash to fund the ADU. This can be advantageous if current interest rates are lower than the existing mortgage rate, but it resets the mortgage term.

- Construction Loan: A short-term loan specifically designed for new construction or significant renovations. Funds are disbursed in draws as construction milestones are met. These loans typically convert to a permanent mortgage upon completion.

- Personal Loan/Unsecured Loan: Not secured by collateral, these often have higher interest rates but offer quicker access to funds and do not put the home at risk. Suitable for smaller ADU projects or bridging financial gaps.

- ADU-Specific Loan Programs/Government Incentives: A growing number of states and municipalities are offering specialized loan programs, grants, or low-interest financing to encourage ADU development, particularly for affordable housing initiatives. Homeowners should research local and state programs.

- Private Funding/Savings: Using personal savings or loans from family members can avoid interest payments but may limit the scale of the project.

Careful evaluation of interest rates, repayment terms, and closing costs associated with each option is crucial.

5.3 Rental Income Potential and Return on Investment (ROI)

One of the most compelling financial motivations for building an ADU is the potential to generate rental income. In high-demand rental markets, an ADU can command substantial monthly rents, ranging from $1,000 to $3,000+ depending on size, location, and amenities. This income can significantly offset mortgage payments on the primary dwelling, cover the ADU’s construction loan payments, or provide a new stream of passive income.

The Return on Investment (ROI) from an ADU can be calculated by comparing the rental income generated against the total construction costs and ongoing expenses (property taxes, insurance, maintenance). For example, if an ADU costs $200,000 to build and generates $2,000 per month in rent ($24,000 annually), the simple payback period would be approximately 8-9 years, not accounting for interest on loans or appreciation. When considering a long-term investment, the cumulative rental income can easily surpass the initial outlay, making ADUs a lucrative proposition.

5.4 Property Value Impact and Appraisal

Adding an ADU demonstrably increases property value. Data from the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) indicates that properties with ADUs in California show higher median appraised values compared to similar properties without ADUs (fhfa.gov). This value appreciation stems from the added habitable square footage, the income-generating potential, and the increased utility and flexibility of the property. The exact increase in value will depend on local market conditions, the quality of the ADU, and its rental income potential.

Appraising properties with ADUs can present unique challenges, as comparable sales (comps) might be limited in some areas. Appraisers rely on the ‘income approach’ (valuing the property based on its income-generating potential) and the ‘cost approach’ (valuing based on the cost to rebuild) in addition to the traditional ‘sales comparison approach.’ The growing acceptance and legality of ADUs are making appraisal processes more standardized.

5.5 Tax Implications

ADU investments have several tax implications:

- Property Taxes: The addition of an ADU will likely increase the assessed value of the property, leading to higher annual property taxes. The extent of this increase varies by jurisdiction and assessment methods.

- Rental Income Tax: Rental income generated from an ADU is taxable. However, homeowners can deduct legitimate expenses associated with the ADU, such as mortgage interest, property taxes, utilities, insurance, maintenance, and depreciation. It is crucial to consult with a tax professional to understand specific obligations and deductions.

- Capital Gains Tax: When the property is eventually sold, the portion of the gain attributable to the ADU (if it was used as a rental) may be subject to capital gains tax. However, primary residence capital gains exclusions may apply to the main dwelling.

In summary, ADUs represent a powerful financial tool for homeowners, offering a pathway to increased wealth through property appreciation and consistent rental income, while simultaneously addressing broader housing market needs.

Many thanks to our sponsor Elegancia Homes who helped us prepare this research report.

6. Social and Economic Impacts

Beyond individual financial gains, Accessory Dwelling Units exert profound social and economic impacts, contributing to more resilient, equitable, and sustainable communities. Their influence extends across housing affordability, demographic shifts, local economies, and environmental sustainability.

6.1 Enhancing Housing Affordability and Supply

ADUs are increasingly recognized as a vital component in addressing the persistent housing affordability crisis. By providing additional housing units on existing residential lots, they contribute to the housing supply without requiring new land development or extensive public infrastructure expansion (habitat.org). This ‘gentle density’ approach increases the available housing stock in desirable, often transit-rich, neighborhoods where large-scale development might be infeasible or politically contentious.

ADUs often represent a form of ‘naturally occurring affordable housing’ (NOAH). Because they are built by homeowners, often with lower overhead costs than large developers, and can be smaller units, they tend to be rented at more attainable price points than newly constructed apartment units. This creates a broader spectrum of rental options, particularly for individuals and families who are priced out of conventional apartments or single-family homes. They can serve as entry-level housing for young professionals, students, or individuals seeking more compact and efficient living spaces, thereby diversifying the housing market and enhancing economic accessibility within communities.

6.2 Facilitating Multi-Generational Living and Caregiving

ADUs are exceptionally well-suited to support multi-generational living arrangements, a growing necessity in an aging society and increasingly diverse family structures. They enable families to live in close proximity while maintaining essential privacy and independence (actonadu.com). This arrangement offers numerous benefits:

- Aging in Place: Seniors can live independently near family members who can provide support, companionship, and care as needed, avoiding expensive assisted living facilities and maintaining community ties.

- Support for Young Adults: Adult children can reside in an ADU while attending college, saving for a down payment, or starting their careers, reducing financial burdens on both generations.

- Caregiver Housing: An ADU can provide dedicated, private housing for live-in caregivers for elderly or disabled family members, fostering a supportive environment.

- Enhanced Family Bonds: Proximity can strengthen familial relationships, allowing for more frequent interactions, shared meals, and mutual support networks.

This living model can also alleviate financial pressures on families by sharing costs and responsibilities, while promoting social cohesion and support within a single property.

6.3 Boosting Local Economies and Community Resilience

The construction and ongoing operation of ADUs have tangible economic benefits for local communities. Construction projects generate jobs for architects, contractors, tradespeople (plumbers, electricians, carpenters), and material suppliers, injecting capital into the local economy. Beyond construction, the increased population density, albeit gentle, can support local businesses, increasing foot traffic and patronage for shops, restaurants, and services within existing neighborhoods. This contributes to a more vibrant and economically robust local commercial ecosystem.

Furthermore, ADUs contribute to community resilience (finance-commerce.com) by fostering a more diverse housing stock capable of adapting to changing demographic and economic conditions. By offering flexible housing options, communities become better equipped to absorb population fluctuations, accommodate evolving family structures, and provide housing for essential workers, thereby creating more stable and adaptable neighborhoods.

6.4 Advancing Environmental Sustainability

ADUs are inherently sustainable in their approach to urban development. They embody principles of infill development and efficient land use, directly combating urban sprawl and its associated environmental detriments (finance-commerce.com). Key environmental benefits include:

- Reduced Urban Sprawl: By increasing density within existing developed areas, ADUs reduce the pressure to develop pristine natural landscapes or agricultural land on the urban periphery.

- Efficient Infrastructure Use: ADUs leverage existing public infrastructure (roads, utilities, public transit, schools, parks), minimizing the need for costly and environmentally impactful expansions of these systems.

- Reduced Transportation Emissions: By enabling more people to live closer to jobs, services, and public transit, ADUs can decrease reliance on private automobiles, leading to reduced vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and lower greenhouse gas emissions.

- Smaller Ecological Footprint: ADUs typically have a smaller physical footprint than traditional single-family homes, requiring fewer materials for construction and often consuming less energy and water for operation, especially when designed with sustainability in mind.

- Encouraging Sustainable Lifestyles: Living in a more compact space can promote more mindful consumption habits and a reduced overall ecological footprint for occupants.

By integrating these units thoughtfully, communities can move towards a more sustainable urban form that conserves resources, reduces pollution, and enhances quality of life.

Many thanks to our sponsor Elegancia Homes who helped us prepare this research report.

7. Challenges and Considerations

Despite their myriad benefits, the widespread adoption and successful integration of Accessory Dwelling Units are not without challenges. These often stem from regulatory complexities, community perceptions, and existing infrastructure limitations.

7.1 Regulatory Barriers and Bureaucratic Hurdles

While significant progress has been made in easing ADU regulations in many regions, especially in states like California, persistent regulatory barriers continue to impede broader development (newamerica.org). These can include:

- Overly Restrictive Zoning: Despite state mandates, some local jurisdictions may still impose subtle or indirect restrictions such as excessive minimum lot sizes, stringent design review processes, or complex permitting requirements that act as deterrents.

- High Impact Fees: Even with some reductions, the cumulative burden of impact fees for utilities, schools, and parks can still be substantial, disproportionately affecting smaller, more affordable ADU projects.

- Complex Permitting Process: Even when laws are more permissive, the sheer complexity of navigating multiple municipal departments (planning, building, public works, fire) can be daunting for individual homeowners who lack experience with construction projects. This can lead to lengthy approval times and increased costs.

- Inconsistent Enforcement and Interpretation: Variations in how city staff interpret and apply regulations can lead to confusion, delays, and frustration for applicants. Lack of clear, standardized guidelines can create uncertainty.

- Utility Connection Challenges: Securing necessary utility hookups (especially sewer capacity) can be technically challenging and costly in older neighborhoods or areas with aging infrastructure. The requirement for separate utility meters can add significant expense.

Overcoming these barriers requires ongoing advocacy for policy reforms, development of clear and accessible guidance documents for homeowners, and continued efforts by municipalities to streamline their internal processes.

7.2 Community Acceptance and Perceptions

Community opposition, often encapsulated by the ‘Not In My Backyard’ (NIMBY) sentiment, remains a significant hurdle for ADU expansion. Concerns frequently voiced by existing residents include:

- Increased Density: Fears that adding more units will fundamentally alter the low-density, single-family character of neighborhoods, leading to overcrowding.

- Parking Congestion: Concerns about increased on-street parking demand, particularly in areas where off-street parking is limited.

- Traffic Volume: Perceived increases in local traffic due to more residents.

- Noise and Privacy: Worries about additional noise, loss of privacy, and changes in the quiet residential ambiance.

- Strain on Public Services: Belief that more residents will overburden local schools, parks, and other public amenities.

- Property Values: While data generally suggests ADUs increase property values, some residents may fear a decrease due to perceived negative impacts on neighborhood character.

Addressing these concerns requires proactive community engagement, transparent communication from local governments about the actual impacts of ADUs (which are often minimal given their small scale), and emphasizing the benefits, such as increased housing options for family members or caregivers, and supporting local businesses. Education can help shift perceptions from fear of change to an understanding of ADUs as a form of gentle, incremental growth.

7.3 Infrastructure Strain

While ADUs are designed to leverage existing infrastructure, a rapid or widespread increase in their numbers can place additional demands on local municipal services and infrastructure (homeoptionssd.com). This includes:

- Water and Wastewater Systems: Increased demand on potable water supply and sewer treatment capacity, particularly in older neighborhoods with aging pipes.

- Stormwater Management: More impervious surfaces from ADU foundations or driveways can increase stormwater runoff, requiring robust drainage systems.

- Electrical Grid: Additional dwelling units place increased load on existing power lines and transformers, potentially requiring upgrades.

- Public Transportation: While ADUs can encourage transit use, an increase in residents may necessitate expanded public transit routes and frequency.

- Public Services: Potential for increased demand on emergency services (fire, police), schools, and recreational facilities.

Effective urban planning and capital improvement programming are essential to anticipate and mitigate these potential strains. This involves regular infrastructure assessments, strategic investments in upgrades, and potentially linking ADU development to infrastructure improvements where appropriate.

7.4 Financing Barriers

Despite the availability of various financing options, securing loans for ADU construction can still be challenging for some homeowners. Lenders may be hesitant if the homeowner’s debt-to-income ratio is high, or if the property’s existing equity is insufficient. Furthermore, appraisal practices, while improving, can sometimes undervalue the potential income or market value added by an ADU, making it harder to secure favorable loan terms.

7.5 Contractor Availability and Expertise

As ADU demand grows, finding qualified and experienced contractors who specialize in ADU construction can be difficult. Building an ADU involves navigating specific zoning rules, integrating new structures with existing ones, and understanding unique small-space design challenges. A shortage of skilled builders can lead to higher costs, longer timelines, or lower quality outcomes.

Addressing these challenges collectively requires a multi-faceted approach involving legislative reform, community education, proactive urban planning, and innovative financial solutions to fully unlock the potential of ADUs as a cornerstone of future housing strategies.

Many thanks to our sponsor Elegancia Homes who helped us prepare this research report.

8. Conclusion

Accessory Dwelling Units represent a remarkably versatile and increasingly indispensable solution to multifaceted housing challenges facing contemporary societies. As demonstrated throughout this report, their benefits are extensive, ranging from a critical contribution to increasing the housing supply and enhancing affordability to fostering more robust multi-generational living arrangements and bolstering community resilience. Furthermore, the inherent design and siting of ADUs align strongly with principles of environmental sustainability, promoting efficient land use and reducing reliance on sprawling development patterns.

However, the full realization of ADUs’ transformative potential hinges upon the diligent and concerted efforts to address persistent regulatory barriers, foster genuine community acceptance, and proactively plan for necessary infrastructure enhancements. The shift from restrictive zoning to more permissive and even encouraging policies, as exemplified by progressive legislation in states like California, is a crucial first step. Yet, legislative intent must be translated into streamlined, transparent, and user-friendly permitting processes at the local level. Simultaneously, effective community engagement and education are paramount to assuage legitimate concerns about density and change, transforming potential opposition into support for flexible housing solutions that benefit all residents.

Ultimately, by thoughtfully embracing ADUs and integrating them strategically into comprehensive urban planning frameworks, communities can proactively move towards creating more inclusive, sustainable, and adaptable housing landscapes. These smaller, adaptable dwellings are not merely an architectural trend; they are a fundamental component of a responsive housing ecosystem, capable of meeting the diverse and evolving needs of a dynamic population while simultaneously preserving neighborhood character and promoting a more resource-efficient urban future.

Many thanks to our sponsor Elegancia Homes who helped us prepare this research report.

References

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Secondary_suite

- habitat.org/our-work/impact/affordable-accessory-dwelling-units-evidence-brief

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/California_Senate_Bill_1534_%281982%29

- huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr-edge-trending-072425.html

- axios.com/local/seattle/2023/07/12/seattle-accessory-dwelling-units

- finance-commerce.com/2023/06/accessible-dwelling-units-offer-sustainable-solution-to-housing-crisis/

- birkesbuilders.com/blog/all/use-cases-for-accessory-dwelling-units

- fhfa.gov/blog/statistics/trends-in-median-appraised-value-for-properties-with-accessory-dwelling-units-in-california

- actonadu.com/blog/use-of-adus-for-multi-generational-families

- newamerica.org/future-land-housing/blog/beyond-accessory-dwelling-units/

- homeoptionssd.com/the-rise-of-adus-and-multi-generational-housing/

Given the increasing prevalence of multi-generational living, how are ADU designs adapting to accommodate the specific needs and privacy requirements of both older and younger family members sharing a single property?

That’s a great point! We’re seeing designs incorporate features like separate entrances, adaptable floor plans, and soundproofing to create distinct living zones within an ADU. Universal design elements are also becoming more common to ensure accessibility for all ages and abilities. It’s about creating a harmonious balance of togetherness and independence.

Editor: ElegantHome.News

Thank you to our Sponsor Elegancia Homes

This report highlights ADUs as a means to increase housing supply. How effectively can ADUs address housing shortages in densely populated urban areas with limited space for additional construction?

That’s a really important question! Infill development, while beneficial, does face spatial limitations. We’re seeing innovative approaches like JADUs and above-garage units becoming more popular to maximize space on existing lots. Thoughtful urban planning that incentivizes ADU construction while addressing infrastructure concerns is crucial for their effective integration.

Editor: ElegantHome.News

Thank you to our Sponsor Elegancia Homes

This is a comprehensive overview of ADUs. Could the report elaborate on how ADU construction financing differs for homeowners versus real estate investors, especially concerning loan types, interest rates, and qualification requirements?

That’s an excellent point about financing! The lending landscape definitely shifts between homeowners and investors. Investors often have access to different loan products like commercial loans, and their qualifications are heavily based on the potential ROI of the ADU as a rental property. This is an area we’ll explore further in future content! Thank you for the suggestion.

Editor: ElegantHome.News

Thank you to our Sponsor Elegancia Homes

The report mentions community resistance. Are there any innovative community engagement strategies that have proven effective in easing NIMBYism around ADUs, perhaps turning neighbors into ADU advocates?

That’s a really insightful question! Successfully navigating NIMBYism often hinges on demonstrating the benefits ADUs bring to the community. One approach involves showcasing real-life examples of thoughtfully designed ADUs that enhance neighborhoods and provide much-needed housing options. Another is facilitating open forums where residents can voice concerns and have them addressed directly by planners and homeowners. Thanks for sparking this discussion!

Editor: ElegantHome.News

Thank you to our Sponsor Elegancia Homes

So ADUs are granny flats, got it! But does that mean I need to start knitting or baking cookies to qualify as a resident? Asking for a friend who prefers coding to crafting…